This essay contains plot details.

by Brant Short

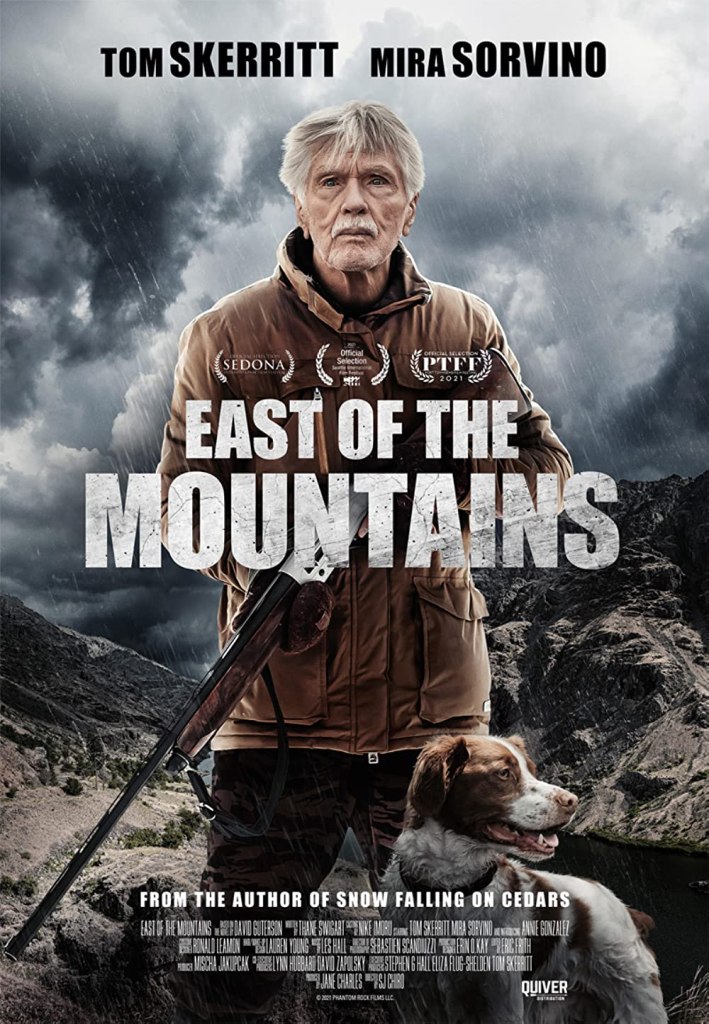

East of the Mountains explores the end-of-life decisions that most of us will confront, regardless of whatever demographic group defines us. These decisions are not only difficult to contemplate, but even more difficult to discuss with others. Do we have any responsibility to loved ones when our life is ending? Should our final wishes be honored regardless of the consequences for others? Is it fair to exclude those closest to us in life from the manner in which we end that life? East of the Mountains considers these questions in a film that is often slow, deliberate and contemplative. Based on a 2004 novel, East of the Mountains is set primarily in rural eastern Washington, a region that is both a high plains desert and a rich agricultural area.

Ben Givens is a retired cardiac surgeon living in Seattle. In the first minutes of the film, we see his daily routine: awaken, eat breakfast, clean the dishes, and go about his day in silence. We learn that Ben is a widower who has received a cancer diagnosis. Without treatment, he may have a year to live. Clearly contemplating suicide, he packs his car with camping and hunting gear and departs for eastern Washington to hunt birds. He is accompanied by his hunting dog Rex and tells his daughter he will be gone for just a few days.

The emotional power of East of the Mountains emerges in long stretches of silence as Ben is often alone, forced to relive his life through memories or to be awakened from dreams of the past. The film’s story arc often moves though imagery in place of orality as its narrative framework. For example, when Ben encounters people on his journey, he is reticent, sharing as few details as possible. It becomes clear that Ben keeps his emotions to himself and seeks independence, regardless of the cost to others. This is clearly a lifetime habit, not simply the result of his illness. When his daughter inquires about his health, he says that it is none of her business. When others inquire about his hunting trip or his life in general, he offers little substance and retreats to silence.

The hunting trip may offer Ben a chance to end his life before he becomes a burden for others as the cancer advances. But his quest to control his destiny is interrupted several times and he is forced to accept help from others. When his car breaks down on an isolated stretch of highway, a free-spirited couple with no apparent schedule gives him a ride. He shares little with the couple but clearly sees their joy in each other and life in general in the short time he travels with them. He does not concern himself with his disabled vehicle and simply wanders into the wilderness, telling the couple not to worry.

Ben’s plan is upset again when his dog is attacked and in a violent confrontation with a coyote hunter Ben loses his shotgun. Alone in the wilderness, Ben is forced to carry a wounded Rex for more than a full day and night seeking help. Once again a stranger appears, stopping on a lonely and dark country road. Seeing Ben in complete exhaustion cradling Rex, the Good Samaritan takes Ben to a nearby town for help. In another act of kindness, the local veterinarian, Anita Romero, opens her clinic after hours, treats Rex, and helps Ben find a motel. Later Anita and her adult nephew offer Ben warmth and hospitality, without any sense of reciprocity or obligation.

Anita’s openness about her life and personal struggles prompts Ben to share his cancer diagnosis and decision to forgo treatment because of the pain it inflicts. Showing concern for this decision, Anita says “you never know” about the outcome. Ben’s reply is forceful, almost angry: “But I do know.” He then lists the painful and difficult side effects of chemo based not only his medical experience but from memories of his wife’s final days in a hospital bed. Although unstated, it is clear Ben does not want that experience repeated with his daughter.

Unwilling to give up on his plan to end his life, Ben must once again seek assistance. He turns to his estranged brother Aiden who stayed on the farm to help the family while Ben went to medical school, married his first love, and had a successful career. Ben’s focus on self and career becomes apparent as the brothers have an awkward lunch. Aiden shares his anger about giving up his dreams to care for their aging father and his anger that Ben never offered help. “I was there for dad in the end. I needed you to be there for me.” With past hurts expressed and nothing left to say, they depart, but acknowledging their concern for each other in a simple handshake and Ben saying, “I’m glad I came.”

Seeking to complete his journey, Ben engages in another violent confrontation to retrieve his shotgun from the coyote hunter who took the weapon. Although he succeeds and finally has the gun in his hands, memories of meeting his wife as teenagers and being part of their shared rural community give him pause. He remembers life as a child with his brother and his father teaching him how to shoot a gun. These memories force Ben to reconsider the important people in his life and the consequences of ignoring loved ones in his final days.

Imagery is important in understanding Ben and the challenges he confronts. The film begins in Ben’s home, a comfortable and traditional space with light colored walls, few ornaments, and many framed photographs of family. Ben’s life is clearly not defined by excess, status, or wealth. Photographs of his wife and daughter point to the priorities in his life, but little else in the home calls attention to a person with some degree of wealth.

Even more stark is the transition from urban Seattle to rural eastern Washington, where Ben was raised and met his wife. The film opens with images of the city, surrounding lush green forests, deep river gorges, and classic mountain peaks. In contrast as he drives across the state the landscape changes to a desert, dominated by rolling hills with high grasses and sagebrush in every direction and very few trees. This is the place of agriculture, small towns, and economic challenge, not the world of a successful surgeon in a major city. Ben does not say he sought to escape this lifestyle, only that he felt a calling to be a doctor when he served in the Korean War. But he never came back for his parents and or his brother when they needed him.

Dialogue is often replaced by Ben in thought: contemplating his next step or becoming overwhelmed with memories. This form of storytelling reinforces the merger of past and present that defines human existence. Writers talk about “interiority” or the quality of telling a story through the thoughts of a character and not simply through their actions. East of Mountains uses interiority throughout the film to portray Ben’s struggle in maintaining control of his last few months or years of life. This is revealed in poignant memories of his childhood, his budding romance with his future wife, as well as her painful death from cancer just a year earlier. His struggle for autonomy and control is also revealed in his face, his posture, and his physical exhaustion. We do not need an explanation of his pain and frustration, we see it in his body.

Ultimately, East of the Mountains asks us to consider the importance of others in our life and the need to share our thoughts and feelings at the darkest times. While many people understand this need at an intellectual level, it is often lost when social media and cyber interactions define much of our interpersonal communication. The emotional investment we offer to the people in our life is often not reciprocated in a society which prioritizes status, wealth, and power.

Ben was a successful heart surgeon, living in a glamorous city, with a daughter who cares deeply about him. Yet when he should have found solace in the love of his daughter and grandson and should have found a way to restore contact with his estranged brother, he turned inward, seeking control of his last days. But unlike many people, Ben received an epiphany and was offered a chance to see that his end journey could take a different turn. East of the Mountains is neither flashy nor melodramatic in its final outcome. Instead, its message is both relevant and substantive and well worth our consideration, especially as all of us will be walking this path someday.