Readers Note: This essay contains plot details

By Brant Short

Besides the annual visits of Charlie Brown, the Grinch and Rudolph the Reindeer, fans of Christmas have an unlimited number of choices for Christmas films and television shows. With cable television and streaming services providing links to hundreds of titles, one can get lost looking for that perfect film for the season. The internet is filled with hundreds of recommendations of the best (or worst films) available.

I’ve watched many of these films and could create my own top ten list, but I’ll leave that task to others with more time and energy. However, there are two films that capture the meaning of Christmas for me that I watch every year. These films are somewhat hard to find and, in my opinion, under-appreciated. Set in the nineteenth century American West, each film tells the Christmas story from the perspective of the Western genre.

These films don’t rely on special effects, stunt casting, or big production values. Instead they offer sentimental stories that affirm the power of Christmas as a personal, cultural, and spiritual ideal: “to give up one’s very self – to think only of others – how to bring the greatest happiness to others – that is the true meaning of Christmas” (American Mercury Magazine, 1889).

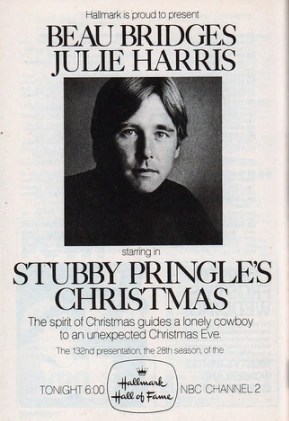

Stubby Pringle’s Christmas

This film aired as a Hallmark Hall of Fame television special in 1978. It is based on a short story by Jack Schaefer, who wrote the novel Shane (1948), the basis for the 1952 film Shane which many people believe to be one the best Western films ever made.

Stubby Pringle is a young cowboy with unbridled optimism. We see him in the bunkhouse with two old-timers on the day of Christmas eve. Stubby has been planning for months to attend the Christmas dance in the community schoolhouse, a twenty-mile ride by horseback. He has purchased gifts (a box of chocolates and a bolt of dress fabric) for a young woman he met the year before and hopes to see again.

The Christmas eve dance is a celebration of community that Stubby looks forward to for months. It gives him a chance for romance and the opportunity to eat sweets, dance, and sing, everything a cowboy can’t do stuck on the ranch.

But on his night-time ride to town he encounters a farm wife chopping wood in a blizzard. He learns that her husband is very ill, their life has been hard, and they have two small children with nothing to celebrate Christmas. Stubby’s plans change as he offers the gifts of time, labor and emotional support to the farm wife with a broken spirit.

Stubby Pringle embodies the spirit of Christmas in different ways. When he asks the farm wife about her tree and presents, she is defensive, she has nothing and replies, “Did you always have a Christmas tree?” “I never did,” replies Stubby, “that’s how come I know it’s important.” He believes that children need a Christmas tree with gifts from Santa Claus, in part because he didn’t have Christmas as a child. Instead of bitterness for his bad turn in life, he embraces the holiday with childlike enthusiasm.

Stubby shares his positive outlook on life with everyone he encounters, from his bunk mates to the wife of his boss, the lonely farm wife, and even the janitor cleaning up after the dance has concluded. It reflects the sense of hope that Christmas symbolizes for many, but it transcends December 25 and is Stubby’s philosophy of life; he lives Christmas 365 days a year. After Stubby describes the hard life of the cowboy and all the “brothers” he knows who have died from pneumonia, cold, heat and even guns, the farm wife observes that he seems to think about death a lot. Stubby’s response is powerful: “No ma’am, no, I think mostly about life because I love it. There ain’t nothing better than waking up and knowing you got a chance at another day.”

The production embraces the Western genre in many ways, from the 19th century language used by Stubby and others to the casting of character actors with a large body of work in Hollywood Westerns (Strother Martin, Chill Wills).

Beau Bridges plays Stubby Pringle with a sense of unlimited energy that feels natural for a young cowboy who works hard, cares about others, and hopes for a better life in the future, all of which affirm the ideal of the American Western.

Ebenezer (1998)

A Christmas Carol has been retold in countless ways with a host of actors taking on the role. An internet search provides many recommendations for the best and/or worst film versions of the classic story. George C. Scott. Patrick Stewart, and Guy Pearce have appeared in versions committed to historic accuracy while Bill Murray, Jim Carey, Michael Caine, and Henry Winkler appeared in other interpretations of the story. Even a futuristic sci-fi version written by Rod Serling aired in 1965 (Carol for Another Christmas).

Ebenezer appears to be a classic Hollywood gimmick: set the story of Scrooge in the Old West and portray him as a villain right out of the archetypal Western. “Bah, humbug” is replaced with “hogwash” and Scrooge is decked out in black, including his hat. But there is something working in this film that sets it apart from other versions of A Christmas Carol. The story is not simply retold in a dusty 19th century town with cowboys and dance hall girls and gun slingers. The Western genre provides depth to the narrative and in turn enhances the power of the original story.

Scrooge is played by Jack Palance, who achieved prominence as the hired gun in the film version of Shane. Nominated for an Academy Award for this breakout role, Palance made a career by portraying villains.

Ebenezer Scrooge is a liar, cheat, and thief, who deceived his father-in-law and lost his wife, swindled his dead partner’s daughter out of her inheritance, and cheated at cards to gain a ranch and a horse from a naïve cowboy. When confronted by his enemies, he turns to physical violence including a willingness to use a gun to get his way.

Ebenezer was filmed in Canada and the plot explains that Scrooge went from his home in Philadelphia to the West to make his fortune, and after cheating his father-in-law by selling his ranch, he goes to Canada in search of gold. He owns the local saloon where he spends his days gambling and treating bartender Bob Cratchit as an object of ridicule.

Scrooge isn’t impressed by the visit of Jacob Marlow (Marley) and his warning to change his ways before it is too late. Scrooge’s response to Marlow is a loud and exaggerated “Blah, blah, blah.” He makes it clear that he doesn’t fear the prospect of visiting spirits. To prepare, he cocks his rifle and dares any ghost to “take your best shot.”

The Ghost of Christmas Past addresses a larger issue than Scrooge’s personal history. Played by a First Nations (Cree) woman, the mere presence of a native figure gives Scrooge pause. “Are you Pocahontas” he asks. The spirit replies, “No, but I have met her” and she informs Scrooge of her mission. “I didn’t know you people celebrated Christmas” he observes. In an affirmation of the larger meaning of the holiday, the spirit says, “We may not call it Christmas, but we do celebrate friendship and family and love on many levels, but since the arrival of you people the notion of exchanging gifts seems rather appealing.”

The Ghost of Christmas Present uses horseback to transport Scrooge to see the struggles of others in his community and the Ghost of Christmas Future is the faceless, hooded figure that inhabits nearly every version of A Christmas Carol. Both ghosts perform their duty by showing Scrooge the truth he ignores in the present and the true consequences if he doesn’t make changes in his life.

As expected, Scrooge is transformed by the experience, but the ending again turns the story around to embrace the Western genre. Instead of simply sharing his good cheer and his wealth, Scrooge is forced to make a life-or-death decision regarding a gun fight of his making. The film ends not with dinner at nephew Fred’s home but in the community center with everyone in town in attendance. Scrooge takes on a new role and hopes the stunned community will forgive him for his many sins against humanity, but the crowd is skeptical. It is only the act of a single child, willing to join Scrooge in a Christmas song, that allows the townspeople to accept and then embrace the transformation of Ebenezer Scrooge.

Christmas and the Cowboy Way

One mark of the lack of appreciation of these films is that they have not been distributed widely. Ebenezer was released as a VHS and later as a DVD but is difficult to locate today. The film used to play on TNT during the holiday season but seems to have disappeared. However, a version with good quality is available on youtube if you are interested.

Stubby Pringle’s Christmas has never been released on video and has not been aired in any form that I am aware of since the 1980s. However devoted fans shared copies for many years. If you are interested, the film is on youtube and currently available.

Rhetorical scholar Janice Hocker Rushing studied the Western Myth as constructed in twentieth century films and television and concluded that at its core, the myth centered on the tension between the individual and the community. This tension is played out in many forms but serves as the primary lens of the Western genre. Christmas gives two very different characters a chance to share and to receive unconditional love from their own unique community.

Stubby Pringle is an orphan who wants something more than working the range by himself. He wants a wife, a family, a home, and Christmas gives him a way to express that inner need with others. While his plans are dramatically changed by his decision to stop and help others, he ends the night with love in his heart. He has achieved the miracle of Christmas in a small way and can continue to hope for more.

Ebenezer Scrooge is the worst kind of person in any community, he holds power over others through money and possessions and that pursuit has grown from greed to evil incarnate. He lives in a town but has no presence in the hearts of the people. It is only when he seeks redemption from the the entire community at the Christmas pageant that he is truly transformed.

Stubby Pringle epitomizes the Christmas ideal in every way: “to give up one’s very self – to think only of others – how to bring the greatest happiness to others – that is the true meaning of Christmas.” Ebenezer Scrooge has taken the first step toward that ideal if we can trust the words of Charles Dickens, “Scrooge was better than his word. He did it all, and more. . . . He became as good a friend, as good a master, and as good a man as the the good old City knew, or any other good old city or town in the good old world.”

If you get the chance this year, take a chance and watch these two films that truly capture the spirit of Christmas and the cowboy way.